Implementaion Level

The current critical literature reflects that international NGOs play a “top-down” role when formulating education initiatives. When these initiatives are implemented in nation–states, international NGOs appear to take on a more collaborative role however the “top down” ideologies and practices still appear to play a dominant part in the collaboration stage. These collaborations are often initiated by coalition/umbrella organizations of international NGOs (Rose, 2006). Although local nation- states and local NGOs are more involved, international NGOs’ tend to have the most power and are better able to implement their agendas for education initiatives. Cultural relevant education can be implement at this level but this depends on the strength, influence and agenda of a government and the presence of strong or weak social capital within a national civil society.

When there is lack of social capital a community’s capacitiy for implementing successful culturally relevant educational programming is weaker. Local NGOs’ (as compared to their international counterparts) appear to have less power and influence in a Global South nation-state; unless they’re agenda is coupled with the values of the national government or an international NGO. The ability of local NGOs to link its social capital with the state and international NGOs will reflect the effectiveness of implementing culturally relevant educational initiatives.

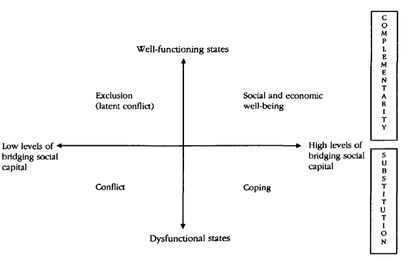

For example the influence of social capital on the effective implementation of educational policies derives from citizens’ attitudes. Successful realization of these policies depends on the acceptance of the initiative by the citizens and their compliance and cooperation with the changes imposed by it. Unless there is a high level of institutional trust created by a linking of social capital then initiatives may not be accepted (James et Al, 2009). The chart below shows how these variances may look. For example when strong governance is linked with the social capital within local civil society a synergy between the state and society can form. In these cases economic prosperity and social order are more likely to happen because there is a higher level of institutional trust. However when a society's ability to link social capital disintegrates social groups disconnect from one another, often leaving the more powerful groups to dominate the state to the exclusion of other groups (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000).

When there is lack of social capital a community’s capacitiy for implementing successful culturally relevant educational programming is weaker. Local NGOs’ (as compared to their international counterparts) appear to have less power and influence in a Global South nation-state; unless they’re agenda is coupled with the values of the national government or an international NGO. The ability of local NGOs to link its social capital with the state and international NGOs will reflect the effectiveness of implementing culturally relevant educational initiatives.

For example the influence of social capital on the effective implementation of educational policies derives from citizens’ attitudes. Successful realization of these policies depends on the acceptance of the initiative by the citizens and their compliance and cooperation with the changes imposed by it. Unless there is a high level of institutional trust created by a linking of social capital then initiatives may not be accepted (James et Al, 2009). The chart below shows how these variances may look. For example when strong governance is linked with the social capital within local civil society a synergy between the state and society can form. In these cases economic prosperity and social order are more likely to happen because there is a higher level of institutional trust. However when a society's ability to link social capital disintegrates social groups disconnect from one another, often leaving the more powerful groups to dominate the state to the exclusion of other groups (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000).

.

(Woolcock & Narayan, 2000)

For instance, in India national educational polices have aligned with the international agenda. As India has not been able to afford universal primary education, agreements between international and local NGOs’ and the Indian gvernment were contrived. This collaboration created a means to meet many of the national educational needs as global and local civil society have been able to link there social capital to the powers that can implement change. In this situation the Indian government shared similar values with the international NGOs,’ enabling effective collaboration and partnerships (Colclough & De, 2010). Through these efforts educational plans were established to create (for the most part) more westernized systems of education that ensure quicker development and financial stability (Pillay, 2010).

In the case of India, Colclough and De (2010) conducted a study on the benefits that international NGO involvement has had on educational programming. They found that international NGO policy collaboration has had little impact on the establishment or change of Indian policy objectives; it has however had a significant direct impact upon management practice, financial reporting, accounting procedures and monitoring arrangements. International NGOs’ were able to form powerful collaborative partnerships with government. This modality became an integral part for local advocacy, accountability and capacity building. (It should be noted that critics of these collaboration note that there are still few examples of pro-poor and “girl-friendly” education programs that enables all children to go to (and complete) school (Rose, 2009). This may be because proper linking of social capital with excluded groups is not occurring excluding key vulnerable groups from policy planning.)

In the case of India, Colclough and De (2010) conducted a study on the benefits that international NGO involvement has had on educational programming. They found that international NGO policy collaboration has had little impact on the establishment or change of Indian policy objectives; it has however had a significant direct impact upon management practice, financial reporting, accounting procedures and monitoring arrangements. International NGOs’ were able to form powerful collaborative partnerships with government. This modality became an integral part for local advocacy, accountability and capacity building. (It should be noted that critics of these collaboration note that there are still few examples of pro-poor and “girl-friendly” education programs that enables all children to go to (and complete) school (Rose, 2009). This may be because proper linking of social capital with excluded groups is not occurring excluding key vulnerable groups from policy planning.)

However in cases where a government has strength but does not share an agenda with international global society and where the ability of local civil society to link social capital is weak, then negotiation and collaboration has been initiated through collective action by international NGOs’, to pressure governments to recognize their roles (Rose, 2006). In countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malawi, Nigeria and South Africa, the dialogue of umbrella associations with governments has been at best tokenistic or at worst antagonistic, with a tension evident between the desire of international NGOs to influence the government’s agenda and at the same time wanting to deliver there own services without interference. This can often is counterproductive to education initiatives as in some cases proposals for including international NGO provision within development plans are not taken into account, and local NGO provision may be made absent from the government’s plan despite the important role they play in serving the poor (Rose, 2006).

In situation like this NGO representative's may ignore collaboration and overstep their boundaries. In Countries like Ethiopia NGOs’ often need to attain licenses and this process gives international NGOs an advantage over local NGOs because they often operate under memoranda of agreement with donors and the ministry of education, which allows them to avoid registering (Miller-Grandvaux et Al, 2006). This allows international NGOs’ to operate without the collaboration of the local community or government.

In situation like this NGO representative's may ignore collaboration and overstep their boundaries. In Countries like Ethiopia NGOs’ often need to attain licenses and this process gives international NGOs an advantage over local NGOs because they often operate under memoranda of agreement with donors and the ministry of education, which allows them to avoid registering (Miller-Grandvaux et Al, 2006). This allows international NGOs’ to operate without the collaboration of the local community or government.

.

Nihsimuko (2009) argues that when there is strong emphasis on the role of civil society marked by a strong ability to link social capital in the implementation process, then these creates positive collaboration and can lead to more culturally relevant educational programming. Local NGOs, when they have a strong ability to link social capital, have their own understandings of social improvement and are better able to work with vulnerable and marginalized communities. EFA and MDG initiatives in Serria Leone enabled these forms of social capital to grow and connections between the government, local and international NGOs became closer and increased the nation’s ability to deliver primary education.

The presence of strong linking social capital enabled local NGOs to implement development projects and programs funded by their international partners. In this case the local NGOs were able to do most of the delivery of educational programming with the funds provided by international NGOs, as a bilateral and multilateral partnership. This approach has led to international NGOs working on capacity building, as opposed to policy development as there key objective in Serria Leone (Nishimuko, 2009). When local NGOs gain much-needed funds for operations, and in return, work on programs under close supervision of governments and international NGOs’, then local civil society can be seen as mediators, service deliverers, convenient consultants or inexpensive contractors (Nishimuko, 2010.

The presence of strong linking social capital enabled local NGOs to implement development projects and programs funded by their international partners. In this case the local NGOs were able to do most of the delivery of educational programming with the funds provided by international NGOs, as a bilateral and multilateral partnership. This approach has led to international NGOs working on capacity building, as opposed to policy development as there key objective in Serria Leone (Nishimuko, 2009). When local NGOs gain much-needed funds for operations, and in return, work on programs under close supervision of governments and international NGOs’, then local civil society can be seen as mediators, service deliverers, convenient consultants or inexpensive contractors (Nishimuko, 2010.

However, if both the state and the ability of local civil society to link social capital are weak then implementation of international NGO run/sponsored educational initiatives may lead to increased aid dependency, and a domination of neo-liberal agendas. Aid dependency is problematic for the national implementation of education goals in developing countries such as Ghana, as the creation of target specific agendas, such as EFA and the MDGs has increased their dependency on aid. This has decreased Ghana’s autonomy in self-funding its social sectors and control over its educational programming (Strutt & Kepe, 2010). In this situation a weak state and an inability to form strong linking social capital has lead to the hi-jacking of culturally relevant educational programs and the forceful implementation of international NGOs’ agendas (Strutt & Kepe, 2010).

In cases like Afghanistan and Iraq educational services may be based solely on need during times of crisis (Novelli, 2010). When these types educational initiatives happen and get tide into “civil military cooperation policy” implementation of education can have very negative effects. In places like Iraq and Afghanistan where there are current conflicts going on international NGOs have attempted to implement education with a specific emphasis on developing civic-mindedness in young people. In these countries challenges to build capacity and to provide universal access to primary education and literacy are challenged by that fact that these initiatives are implemented from a western perspective without proper collaboration making these programs targets for indigenous forces (like the Taliban(Novelli, 2010). In this case there has been not collaboration with local civil society or governments creating a complete disconnect between education and cultural relativity.

.

The roles of NGOs’ at the implementation stage are varying. NGOs’ can take on the role of collaborator, advocate, or partner as well as bully or oppressor. In each case the success of implementation is based on the strength or weakness of the government and the strength of the ability of a local civil society to link social capital. It seems clear when given the chance the majority of international NGOs’ continue to use the an equal playing field to implement neo-liberal educational initiatives over culturally relevant programs.